First Review in for Freaks of the Wireless

While we're still counting down the days to release, some advanced review copies of Freaks of the Wireless have been sent out, and we're delighted at this glowing review from Dr Stuart Mitchell, Lecturer in History with the Open University and organiser of the Curious Histories series of talks, who have an upcoming London Special on the 28th of April.

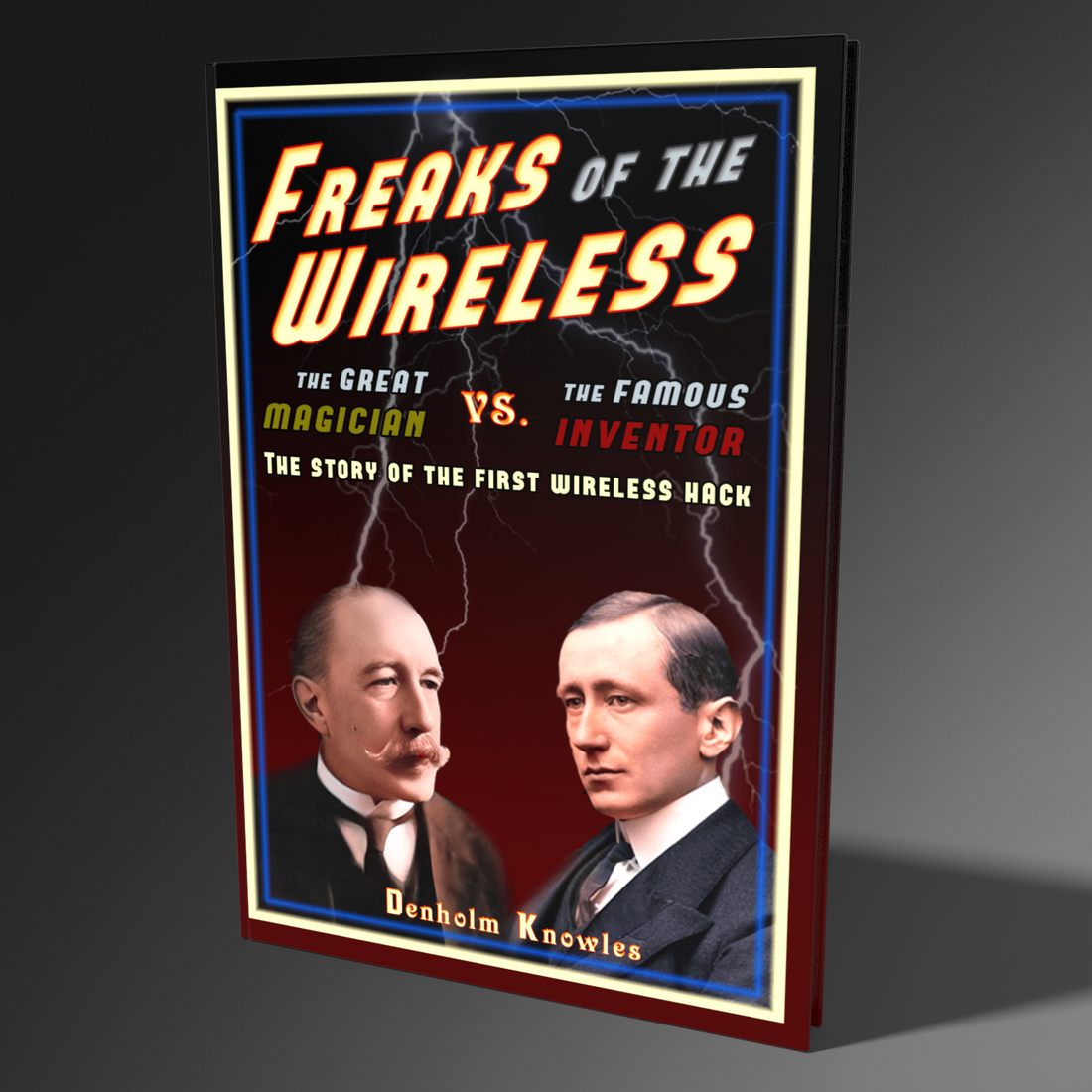

If you imagined that the hazards of information technology – the phishing, spamming, and jamming with which many of us are now painfully familiar – originated in the internet age, Den Knowles’ new book might surprise you. Of course, the past is peppered with examples of promising new technologies that brought immediate attempts to steal, copy, resist, or spoil them, and the early days of wireless communication, the book’s subject, were no different. While there are plenty of works on the history of radio, they tend towards straight narratives. Freaks of the Wireless instead approaches its topic in an unusual way: examining early struggles over the medium’s development through the lens of the rivalry between Guglielmo Marconi and the famous Edwardian magician, Nevil Maskelyne, himself no slouch as an inventor. This contest, which grew increasingly bitter, provides the framework for the volume’s story, and serves up numerous examples of the malicious trickery that today bedevils the online world: literally, the first ever denial-of-service attacks and wireless hacks in history!

The book, then, should appeal not only to readers interested in the history of science but also those involved in IT security. And it provides a potential feast for both. Knowles’ meticulous research informs the text, which draws in primary sources ranging from memoir and personal correspondence through to trade press such as the Electrical Review and even historical weather data. These are knitted together in a sprightly series of chapters which track how radio technology rose in lock-step with Marconi’s and Maskelyne’s mutual antagonism. But this was not, as we might suppose, a dispute played out simply in the pages of niche journals and scientific assemblies; rather, as Knowles explains, it was a highly public feud with many vivid interventions. Two set-pieces stand out. In chapter four, the story of the Carlo Alberto incident, in which ship-to-shore radio communications were jammed during the 1901 America’s Cup, reads like a cross between a drama and a puzzle to be solved. Odder still is the author’s re-telling of a pivotal 1903 wireless telegraphy experiment held at London’s Royal Institution, which was interrupted by virtual vermin and messages with Shakespearean portent. The book commendably manages to balance these moments of spectacle with more reflective analysis and careful description.

Knowles does not shy away from describing the technical aspects of his subject, but for the most part they are delivered with a light-enough touch to be intelligible and interesting to the layperson – besides, there is a rather helpful glossary at the book’s end for those who don’t know phreaking from phishing. Neither does he neglect the wider social and scientific background against which the development of wireless technology took place. The book makes frequent references to the broad technological anxieties – around for instance secrecy, surveillance, business integrity, and economic risk – that were no less characteristic of the Edwardian age than they are of our own. A rich series of illustrations also adds contextual colour, including the delightful frontispieces to each chapter, each designed like a late Victorian playbill. Overall, Freaks of the Wireless is a relatively rare example of a study conducted by an expert in a non-historical field that works just as well in the history discipline.

You can pre-order Freaks of the Wireless, and the special edition, on our site.